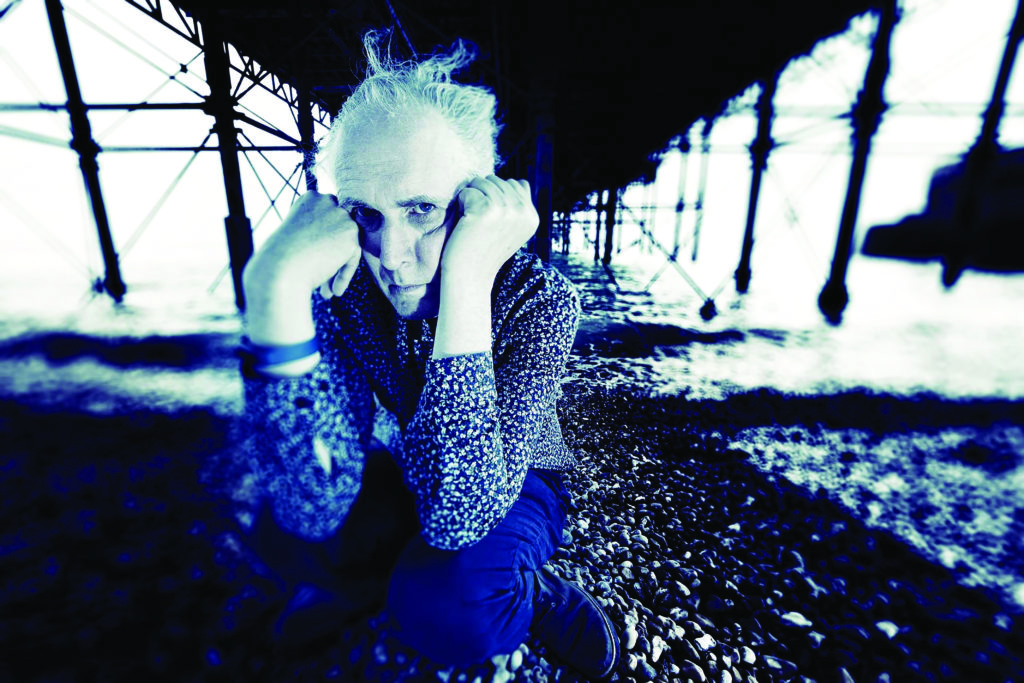

Tim Pope (Photo credit: Andy Vella)

The Hoffman Process speaks to you at a time when you need it, or when you are ready to listen. I know that, because that’s what happened to me.

Here’s the story. My family and I were staying with a pal at her villa in beautiful Umbria, in northern Italy. I had never been to this part of the world before. The house was situated down a dirt track, and from every side the windows let out to glorious views of rolling, vineyard-covered hills.

Daily life in the house, I soon discovered, was pretty communal, with everybody mucking in to cook and to clean up afterwards. In the five days we sere staying there, things just fell naturally into place, without anything necessarily being said or needing to be said.

Occasional lazy forays were organised to go into the nearby town, Città di Castello, which – as the name might suggest – has a castle and has a classic wall about it. Large lunches would be arranged, where members of our hostess’s seemingly endless circle of friends who happened to be in the area would join us before they continued on their journeys.

The specific time I am talking about was such an event and, accordingly, a long table near to the bustling market had been sorted for people to congregate.

I sat myself at one end, as was my way. This felt like the most comfortable place to be and probably meant I would only be forced to interact with people in a controlled way that I’d find easier. I wouldn’t describe myself as unfriendly or antisocial – I (outwardly) appear confident and can be garrulous in the right company – but there has always been a distinct aspect to my character that finds large groups of people uncomfortable.

My partner was sitting beside me and our two kids were at the far end of the table; ‘the children’s end.’ As people arrived to join us a red-haired woman from the UK called Serena sat down next to us. Before long, my other half and her worked out that they had attended the same college, and soon they were exchanging the names of mutual friends and nostalgically swapping tales.

In my usual manner – at which I had become pretty adept – I listened to the hum of the chatter around me from beneath my hat and behind my sunglasses, doing my best not to participate. Meanwhile, our friend was circling the table capturing the event for posterity with her camera. It was her picture of me that truly shocked me later.

A few days or so after this, we were back home in Brighton, where we lived at that time. Despite the wonderful holiday, I found myself back in the pit of despondency where I seemed to reside most of the time. Nothing I could specifically put my finger on here – just a general, constant ‘malaise of unhappiness’ that gnawed inwardly at my soul, unseen by the world. The awful thing was that I had pretty much become accustomed to feeling like this. It had become the ‘norm’, and so it didn’t feel like anything particularly strange or unusual. It didn’t even feel like anything I should – or could – do anything about. In a way, I honestly think I had become comfortable with the idea of being uncomfortable in my life.

I had written to our friend to thank her for our time away and a couple of days later she pinged me an email by return that contained several photographs of our trip, including one of me at that table.

Did a picture ever say a thousand words?

It showed a sad-looking, pissed off creature, whom I hardly recognised as myself. He sat with his hat pulled down to his forehead and with dark glasses hiding his eyes. There was no joy at all to this alien character – even the way the shot had been framed seemed to convey isolation. By coincidence, a sign was over his head, reading ‘TIM’, which is apparently an Italian telecommunications company, but also my name.

The really shocking thing about the image was that it reminded me of the one dead body I had seen – my father’s.

My father died unexpectedly, on vacation in Jamaica. Arranging to have his body shipped back was difficult and complicated, but finally I went to see his remains in a darkened mortuary in north London. What I saw then had really stuck with me. My Dad would have sat up, was always ready to crack a joke; this lifeless, cold thing just wasn’t him at all.

In our friend’s photograph, I instantly saw massive parallels between myself and my Dad in that mortuary. Without realising it, I had turned myself into a sort of living corpse.

For some reason, at the moment I was studying the photo, I recalled the half-heard conversation my partner had been having with Serena at the table. At the time I’d been paying little attention, but now remembered it involved something called the Hoffman Process. In my cut-off state I’d caught the odd word perhaps, but nothing specific. I’d vaguely gathered that it involved some sort of deep, immersive experience to help with the malaise people sometimes felt in their lives.

‘What was that thing you were talking about to that woman in Italy?’ I asked my partner.

Immediately, I looked the Hoffman Process up online. Within the space of two hours, I had grabbed a place on a course in a fortnight’s time at Florence House in Seaford.

I surprised even myself in how quickly I made this choice. I still think that had this message come to me at a different time, a more cynical moment, I may well have ignored my instinct.

Many people will tell you what a profound experience ‘doing the Hoff’ is in their lives and how those few days they gave have changed their lives forever. It definitely ‘reaches the parts other things do not go to’, to paraphrase the old beer advert.

For me, I can tell you it not only did it change things profoundly – a sort of reboot at a DNA level – but it gave me plenty of ‘tools’ which I still use to this day, over ten tears after.

Not for one second would I urge you to do the Process. However, if it seems – perhaps from something you read or hear – to be the right thing for you, I would urge you to listen to yourself.

You will know when the time is right.

You can find out more about Tim and his work on his website: timpope.tv

or on twitter @timpopedirector.

Sign up to receive monthly newsletters from Hoffman

Sign up to receive monthly newsletters from Hoffman