A s someone who grew up between two cultures, I’ve always lived with a fragmented sense of identity. This is hardly rare in today’s world. According to British author Pico Iyer, there are over 220 million ‘third-culture kids’ globally, or those who might not have a simple answer to the question ‘where is home’? But I also felt there was something else going on with me that went beyond an ambiguously-defined feeling of belonging.

s someone who grew up between two cultures, I’ve always lived with a fragmented sense of identity. This is hardly rare in today’s world. According to British author Pico Iyer, there are over 220 million ‘third-culture kids’ globally, or those who might not have a simple answer to the question ‘where is home’? But I also felt there was something else going on with me that went beyond an ambiguously-defined feeling of belonging.

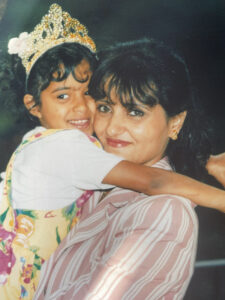

My parents moved to London with me and my four older siblings when I was a few months old. My father’s work, which had brought us there, meant he wasn’t around very much, so my early life revolved around my mother, school and friends. When I was 9 years old, my father was keen for us to return to his homeland, Saudi Arabia, while my mother preferred that we continue our education in London. At this point, a rift occurred that had major repercussions.

My father ultimately took me and my three other siblings who were still in school back to Saudi, and we weren’t allowed to have contact with our mother for the next five years. That early disconnect was the root of many problems that would manifest themselves in various ways in the coming years.

When I first arrived in Saudi, after the novelty of the adventure and excitement about seeing our extended family wore off – and despite my father’s best efforts to make us feel settled – I felt desperately lost and alone. My mother, the person at the centre of my life, was gone, along with my friends and everything that was warm and familiar to me at the time. It was a very dark period.

Thankfully, I gradually managed to make some good friends and form strong bonds with our family there. With their help and the comforting companionship of my dog Melou, Saudi started to feel like home. Indeed, I found myself connecting profoundly with many aspects of my culture and actually enjoying my life, despite the enduring sense of loss and longing I had for my mother.

Thankfully, I gradually managed to make some good friends and form strong bonds with our family there. With their help and the comforting companionship of my dog Melou, Saudi started to feel like home. Indeed, I found myself connecting profoundly with many aspects of my culture and actually enjoying my life, despite the enduring sense of loss and longing I had for my mother.

In 2007 I finished school and decided to go to university back in the UK. I was so overjoyed at the prospect of being close to my mother again that I really felt my life was sorted – that the past was behind me, once and for all.

However, fast forward through my university years, some solo travel, a couple of jobs and relationships, and it dawned on me that I was deeply unhappy. By now in my late 20s, I was feeling even more lost than I was as a child in Saudi all those years ago. I was completely disconnected from myself – more accurately, I didn’t have the slightest idea who I was.

As a defence mechanism, to avoid addressing or acknowledging the hollowness inside me, I would outwardly feign self-confidence and happiness, but inside I was constantly second-guessing, self-criticising, never feeling good enough. I was always seeking fulfilment and validation from outside sources, even if it meant sidelining my own needs or desires. On some level I was aware of this, but felt powerless to do anything to break the cycle.

My career choices, my relationships and how I acted within them – so many of my decisions were made not from a place of inner conviction, but from what I thought would get people to approve of me – or never leave me. At any given moment, this was all swirling like a maelstrom inside me, but I was at a complete loss to properly define or even articulate any of it to the people closest to me. On the other hand, the harsh inner voice would chastise me: I had a family that loved me, great friends, health, all the basics – how could I even think of complaining?

At one point when I felt particularly low and hopeless, I finally decided to try therapy, but found the time and money commitment unsustainable. I was working very long hours at a due diligence company with a lengthy daily commute, and the idea of long-term therapy felt like a never-ending road with potentially inconclusive results. I did manage to make some positive changes in my life though. After realising how unsuited I was to my job, I went part-time and began taking acting classes just for fun, as I’d always had a passion for it as a child.

At one point when I felt particularly low and hopeless, I finally decided to try therapy, but found the time and money commitment unsustainable. I was working very long hours at a due diligence company with a lengthy daily commute, and the idea of long-term therapy felt like a never-ending road with potentially inconclusive results. I did manage to make some positive changes in my life though. After realising how unsuited I was to my job, I went part-time and began taking acting classes just for fun, as I’d always had a passion for it as a child.

Around this time, my best friend Jumana had just done the Process in Ireland. I sensed a very positive change in her, but couldn’t put my finger on what it was. So when she strongly recommended the Process, I decided to go for it. Jumana isn’t easy to impress and cares about me deeply, so although I arrived at the course feeling extremely nervous, I was also excited and confident I was doing the right thing.

Coming from a culture where we don’t normally speak openly about our feelings and especially our flaws, I found the Process sessions intimidating at first, but as I gained trust with the facilitators and other participants it became easier and easier. In the days that followed, I realised that I’d left behind an important part of me all those years ago. I started hearing a voice I hadn’t heard in more than two decades: my own authentic one, imbued with self-assurance, vivacity and playfulness. Through the introspection, guided expressive work and techniques we did on the course, I finally joined the dots.

I was able to begin processing emotions that were frozen in time, poisoning me and forcing me into a state of constant defensiveness and neediness. From what I now understand to be a legacy of my early experience, my childhood self felt so in need of love, affection and stability from outside sources that I’d bend over backwards to please people or show them what they wanted to see. Like a chameleon, I presented a different Sara tailored for each audience. When I think about it, it was a relatively easy task for someone who didn’t know how to listen to her own inner voice and intuition – or even to locate this voice at all.

I could now see how my childhood fear of being abandoned or rejected meant I tended to hang on too long in relationships, even those that had run their course or become detrimental to me. I realised that the judgmental inner voice was fed by a belief I’d formed all those years ago that I was undeserving of compassion, and was somehow to blame for losing my mother’s care.

I could now see how my childhood fear of being abandoned or rejected meant I tended to hang on too long in relationships, even those that had run their course or become detrimental to me. I realised that the judgmental inner voice was fed by a belief I’d formed all those years ago that I was undeserving of compassion, and was somehow to blame for losing my mother’s care.

Since the Process I’m far more compassionate with myself. I have more respect for myself and my needs – most importantly, I determine these needs and boundaries myself. Instead of filtering or shaping my personality or preferences so that people will like me, I understand that I won’t be everybody’s cup of tea, and that’s fine. I now have the resilience to choose to end negative relationships or situations that don’t serve me. I no longer bottle up my feelings, nor rely on others to feel positive about myself. Jumana, a constant source of strength for me, tells me I’m more confident and stick up for myself more – changes I have noticed too.

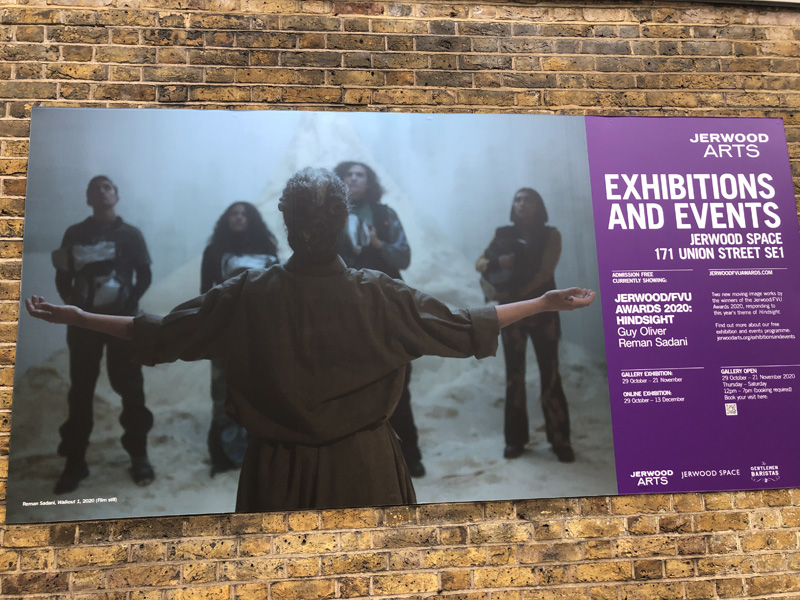

Having reclaimed my childhood self, I’ve been tuning into what it has to say. I finally acknowledged that acting is not just a hobby for me but a coveted dream, and faced my fears of failure in order to really go for it. I made an acting profile and started auditioning for roles, and have since been involved in a few projects. Throughout the UK lockdown I’ve managed to find work in online productions, including a mini-series satirising lockdown for which I wrote my own character. Small steps, but in the right direction.

I’ve been expressing my creativity in different ways: reteaching myself the piano, something else I left behind when we moved from London, and finding more time to write. I also started an Arabic food business with my sister, my other half, who’s a brilliant cook. Filling my time with things that bring me joy has made me lighter and happier than I’ve ever been, and I feel that doors are opening for me.

I know that I don’t have all the answers, and I’ll inevitably face ups and downs, as we all do. But now I finally believe in myself, I trust that I know the best way forward. The compassion, stability and fulfilment I’ve always craved now starts from within. I finally found home – and it’s inside me.

Sara’s Top Tips:

- Make time for yourself that’s non-negotiable and do your own thing. Whether that’s dancing in your room, walking in nature or sitting in silence – prioritise yourself by bringing little parcels of joy, peace or expression into your everyday life.

- When you’re being judgmental and overly critical of yourself, ask yourself whether you’d hold a close friend or someone you love to the same standards. The answer’s usually no.

- When something is eating away at you, do not keep it in. Sometimes just the act of voicing an insecurity or problem – whether spoken to a loved one or just written down for yourself – is all you need for it to start dissipating.

- Don’t dwell in your head! Whenever you catch yourself overthinking minute details you have no control over, eg wondering how you came across to someone or what they might think of you, remember that a lot is probably your own projections. Shake it off, and bring yourself back to the present.

- Make a collage of your favourite childhood pictures, ones where your authentic, unadulterated qualities shine through in all their glory. Hang it up somewhere you’ll always see it, so you never lose sight of your happy inner child.

To watch the mini-series about lockdown, visit: www.youtube.com/isolationtapes

For more of Sara’s creative pursuits follow her on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/saramasry/ or check out her bio, here: https://jacksonfoster.co.uk/sara-masry/

Sign up to receive monthly newsletters from Hoffman

Sign up to receive monthly newsletters from Hoffman