It was supposed to be the complete skillset for living, but despite having trained to be a consultant psychiatrist, dark emotional clouds lingered over many areas of my life.

It was supposed to be the complete skillset for living, but despite having trained to be a consultant psychiatrist, dark emotional clouds lingered over many areas of my life.

It wasn’t that the subconscious was entirely hidden, but the plague of fixated patterns of behaviour persisted iceberg-like, threatening to pierce a gaping flesh-wound pretty much any time, even when things seemed to be plain-sailing. When to find the time and who to trust, to explore below the waterline?

I was dragged up in 1970’s Dublin where, from a very early age, I became aware of my father’s alcoholism. My childhood was shaped by the unpredictability of having a father stagger through the door in a state of intoxication and the constant strain of seeing my mother trying to make ends meet.

I was the youngest of two boys and while my older brother openly clashed with our father, peace-making and feeling overly responsible for my mother was my anointed role within the family unit.

In Ireland at the time, escaping a dysfunctional marriage was not an option, so my mother had to choose to remain in situ, trying to ensure my father met even a portion of his domestic responsibilities. All the while a false veneer of normality and appearances had to be kept up and projected to neighbours and the community – but a sense of shame and feeling very different to other kids was to dominate my early emotional experiences.

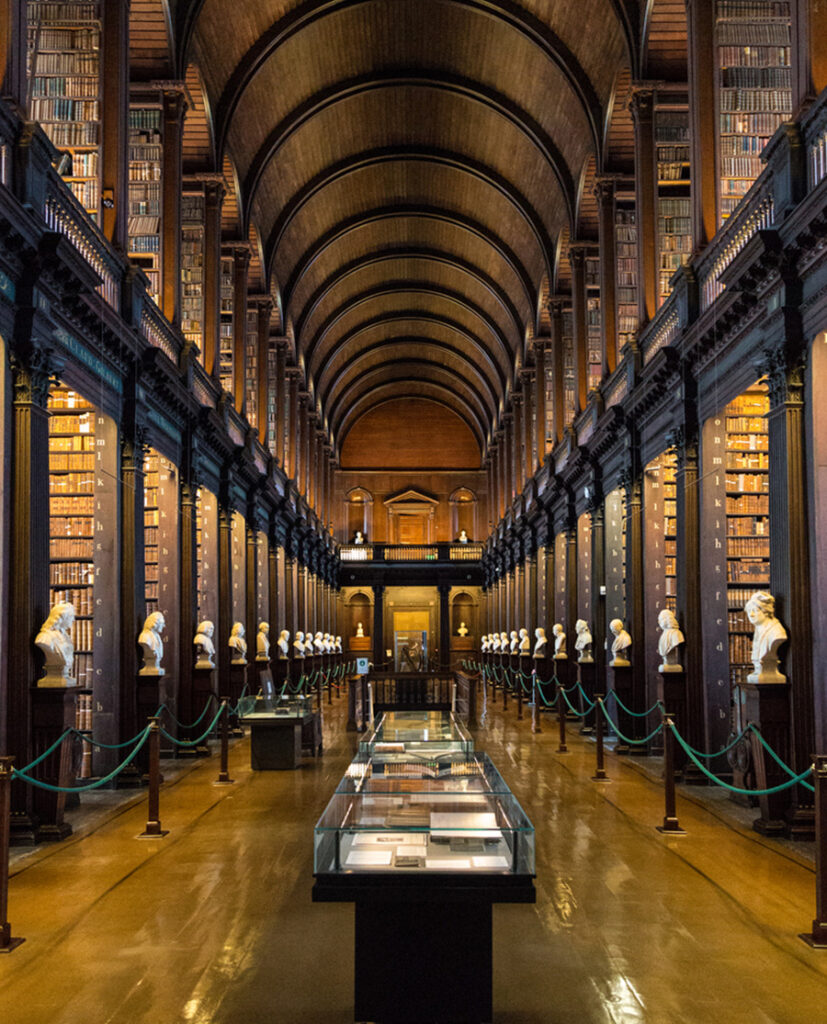

I took refuge in books and a vivid imagination, but shut down emotionally. This was compounded by my mother experiencing severe episodes of depression, requiring hospitalisation. The care and parenting that my father was incapable of providing fell to reluctant aunts and uncles.

I took refuge in books and a vivid imagination, but shut down emotionally. This was compounded by my mother experiencing severe episodes of depression, requiring hospitalisation. The care and parenting that my father was incapable of providing fell to reluctant aunts and uncles.

A safety net was provided by one uncle who was a physician and whose generosity provided a glimpse of what the outcome of a diligent education could be. A key role model, he undoubtedly influenced me in my choice to study medicine at Trinity College Dublin.

The intensity of a medical career and the temporary nature of most early hospital jobs left little time for reflection, but in hindsight, my eventual decision to study psychiatry pointed to a desire to explore the origins of a personal emotional overcontrol and numbness. Moving to London in the late 1990’s afforded career-enriching experience and was where I met my wife – also a hospital consultant from Ireland. Together we have two wonderful children and are still happily married after two decades.

However, I now realise that in my approach to my working life, I’d followed my father’s pattern of addiction in order to numb emotion – only in my case work, rather than alcohol, was the emollient. Holding a hospital consultant post offers the potential to tap into a quest for perfection, self-scrutiny and an overwhelming anxiety about patient outcomes and being responsible for others. This set up a very heavy schedule and way of working that left me feeling constantly deprived of energy and imbalanced in many areas of life.

However, I now realise that in my approach to my working life, I’d followed my father’s pattern of addiction in order to numb emotion – only in my case work, rather than alcohol, was the emollient. Holding a hospital consultant post offers the potential to tap into a quest for perfection, self-scrutiny and an overwhelming anxiety about patient outcomes and being responsible for others. This set up a very heavy schedule and way of working that left me feeling constantly deprived of energy and imbalanced in many areas of life.

In 2004, my mother died just as our firstborn arrived prematurely. I knew she was immensely proud of me for taking over from the same doctor that had faithfully looked after her many years previously. The death of my brother by suicide four years later was to be the biggest tragedy of my life and led to an even deeper doubling down and escape into work.

Nonetheless in the background, a lingering feeling that something had to change grew and grew, especially after a physical health scare.

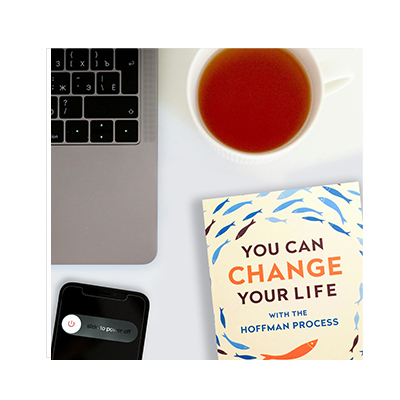

I’d been to a Hoffman introductory evening in Dublin in the early 2000’s with my wife and even recommended the Process to a number of patients, who subsequently described the sense of liberation and freedom it induced. Our children, especially our daughter who was studying for a psychology degree, had been unaware how their uncle had died. Now they’d begun to ask questions about my brother’s death and I knew I couldn’t keep the truth from them for much longer. Finally in November 2023, my wife gifted me the deposit for the Hoffman Process, hoping among other things that it would encourage a physical as well as an emotional de-clutter, as I am a bit of a hoarder!

I’d been to a Hoffman introductory evening in Dublin in the early 2000’s with my wife and even recommended the Process to a number of patients, who subsequently described the sense of liberation and freedom it induced. Our children, especially our daughter who was studying for a psychology degree, had been unaware how their uncle had died. Now they’d begun to ask questions about my brother’s death and I knew I couldn’t keep the truth from them for much longer. Finally in November 2023, my wife gifted me the deposit for the Hoffman Process, hoping among other things that it would encourage a physical as well as an emotional de-clutter, as I am a bit of a hoarder!

I knew the Process was an emotional risk that would involve a lot of initial discomfort, but at this point I was willing to push through that. After completing the course in January 2024, I’m very glad I did. The pre-course work was an insight-building tool and revelatory in itself. The week at the venue in Kent was skilfully constructed, with a lovely balance between silence and expression, using ritual to powerfully reinforce a particular skill or technique. The facilitators were open, receptive, caring and attuned to all our highs and lows. I felt entirely safe in sharing with the group all the way through the week and our mutual vulnerability and openness created the strongest of bonds, as we became more like family to each other than strangers.

The concept of the Quadrinity – that we all have intellectual, emotional, spiritual and physical aspects which require equal attention – struck an intuitive chord with me and will influence my beliefs and practice regarding therapeutic change. The somatic exercises where we released feelings from our bodies was a particular revelation. I believe this emphasis on bodywork and the distraction-free immersion and disengagement from phones and screens was vital. A lot of our group actually dreaded switching their phones back on and delayed it for as long as possible. We had truly gotten back in touch with what we lost when we first had mobile devices – a sense of creative idleness.

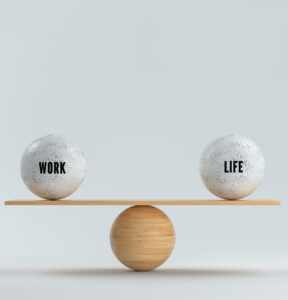

I left the Process unburdened. I started the course as a workaholic and have now put down new ground rules at work. Things feel generally lighter and easier in most areas of life and my wife is delighted to see me home earlier on Friday evenings. I punctuate my days now with mental rest and have reinvested in a social life.

I left the Process unburdened. I started the course as a workaholic and have now put down new ground rules at work. Things feel generally lighter and easier in most areas of life and my wife is delighted to see me home earlier on Friday evenings. I punctuate my days now with mental rest and have reinvested in a social life.

After the Process, I took Hoffman advice and attended all the support groups, as well as following through on my promise to spend more quality time with my children. We’ve already had one successful trip together and have more planned. I spoke to my Hoffman facilitator during the week about how to share the true nature of my brother’s death with my children and she gave me some very helpful advice, so that’s now out in the open. As for the decluttering, it’s happening gently, possibly not at the pace my wife would like, but I’m definitely getting there…

Top Five Process Takeaways

- In any contest between work life and family life, family is always more important and should win every time.

- Showing our mutual vulnerability and disclosing openly will build trust and foster warmer and more authentic relationships.

- Hoffman has stressed the need for the compassion rather than the condemnation reflex. Everyone has struggles, even if they’re not always apparent – so let’s give each other the benefit of the doubt more often.

- Our past struggles don’t define us – they can make us more compassionate and resilient.

- Self-care should never be an optional add-on – it’s the essence of our own and others’ wellbeing.

We’d like to thank Chris* for sharing his story; to read more Process Stories from Hoffman graduates, click here

*Some names have been changed for confidentiality reasons.

Sign up to receive monthly newsletters from Hoffman

Sign up to receive monthly newsletters from Hoffman