I grew up an only child in a council house in an industrialised area of the North West of England. My Mam did factory work and cleaning jobs and my Dad was a labourer, mainly on building sites. He was deaf in one ear, so he yelled rather than spoke. Often we’d get whacked for things he’d imagined we’d said.

I grew up an only child in a council house in an industrialised area of the North West of England. My Mam did factory work and cleaning jobs and my Dad was a labourer, mainly on building sites. He was deaf in one ear, so he yelled rather than spoke. Often we’d get whacked for things he’d imagined we’d said.

Arguments in the home, mainly about money and my Dad’s other women, were very common and often ended in my Dad shouting and hitting my Mam. He was a big bloke with a short fuse and he became loud, abusive and violent whenever he lost his temper. He constantly ridiculed Mam for his own amusement and ordered me to join in. I would obey as a kid to win his approval. He called me a ‘cissy’ whenever I sought my Mam’s affection, so I stopped doing so.

My mother and I were terrified of Dad when he was angry and peace at home depended on whether he had money or a job. My friends didn’t dare enter the house when he was home. Local, extended family overlooked the domestic violence – they were struggling with their own problems, like most of the neighbourhood. I grew up considering all this normal, but I had no idea how ashamed and inferior it made me feel.

My Mam had a very tough upbringing. After her own mother’s death and subsequent abandonment by her father when she was fourteen, she cared for two of her brothers – one still only a baby and the other a boy with special needs. The eldest had joined the army before the war and by then was fighting in Europe. During my childhood, she was on tablets for depression and made two attempts on her own life.

My father’s life got off to a bad start. When he was three his parents gave him to his grandparents to look after. But within a year his grandfather was killed in a steel works accident and his grandmother passed away. This meant he went back to parents who didn’t want him.

My father’s life got off to a bad start. When he was three his parents gave him to his grandparents to look after. But within a year his grandfather was killed in a steel works accident and his grandmother passed away. This meant he went back to parents who didn’t want him.

Later, the Process helped me forgive my own parents’ flaws as well as show me why I’d been malfunctioning for years.

I grew up very confused. I felt that everything that was happening was some kind of punishment for something I’d done. I just didn’t know what it was. I felt evil and aggressive inside. I was never at ease. I didn’t feel I really belonged anywhere. There were rumours that my Dad wasn’t my real father, which made things worse. I was frustrated and angry.

I turned this rage on my mother. I got into fights and vandalised property. This soothed me – but only temporarily. It was as if I was unleashing some inner demon like Mr Hyde, yet deep down in me there was Dr. Jekyll – another part trying to express itself in a positive, creative way. But still the overriding belief was that everything around me was what to expect from life. I had no idea how it was shaping me as a character. I thought I was the problem because somehow I wasn’t coping.

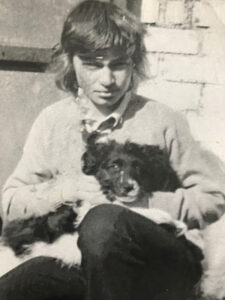

I was one of three kids in a class of forty who passed the eleven-plus exam to go to grammar school. Education was a Godsend because when I was twelve, my father left us for another woman and my mother had a breakdown. A family in our street took me in and most days after school for two months I’d visit Mam in the psychiatric ward. Conditions back then meant I witnessed strange, scary behaviour of other patients on the ward. Luckily I’d just got a puppy that I called Rod after my favourite footballer. My dog was a great comfort to me and it made me feel good looking after an otherwise helpless animal. It made me feel grown up. My other saving grace was school, where lessons and football got me on the straight and narrow. It offered some security and normality.

I was one of three kids in a class of forty who passed the eleven-plus exam to go to grammar school. Education was a Godsend because when I was twelve, my father left us for another woman and my mother had a breakdown. A family in our street took me in and most days after school for two months I’d visit Mam in the psychiatric ward. Conditions back then meant I witnessed strange, scary behaviour of other patients on the ward. Luckily I’d just got a puppy that I called Rod after my favourite footballer. My dog was a great comfort to me and it made me feel good looking after an otherwise helpless animal. It made me feel grown up. My other saving grace was school, where lessons and football got me on the straight and narrow. It offered some security and normality.

It turned out I had a particular gift for languages and certain teachers encouraged me. My Mam got better and was so proud of my scholastic achievements. She took on several cleaning jobs to pay for extra stuff the state didn’t provide. My Dad’s whereabouts were unknown, so there was no maintenance. She made sure I had clean clothes and enough to eat – even though there was often more on my plate than hers. The house was spotless and cosy.

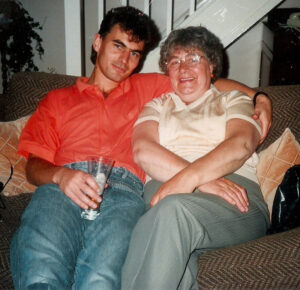

Unfortunately, adolescence arrived with a vengeance. Mam worried when I wouldn’t do as I was told. I stayed out all hours and drank illegally in pubs and dabbled in drugs. I was hooked on the effect because they made me feel like someone else. Despite Mr Hyde, Dr Jekyll ensured I made it to university. Unfortunately on a visit home in my final year, I was beaten up by a gang when I’d been drinking. My facial injuries were so bad that my Mam had another breakdown. Although I gained a BA and then an MA and became a teacher, my self-esteem never increased.

Unfortunately, adolescence arrived with a vengeance. Mam worried when I wouldn’t do as I was told. I stayed out all hours and drank illegally in pubs and dabbled in drugs. I was hooked on the effect because they made me feel like someone else. Despite Mr Hyde, Dr Jekyll ensured I made it to university. Unfortunately on a visit home in my final year, I was beaten up by a gang when I’d been drinking. My facial injuries were so bad that my Mam had another breakdown. Although I gained a BA and then an MA and became a teacher, my self-esteem never increased.

When I married, I became responsible for my wife’s son from her first marriage as well as our own two children. I saw myself in the role of fixer. I was keen to create some semblance of an extended family, so I decided to trace my father. I found him living a sad and lonely life in poverty. He only mentioned the past to badmouth my mother. He died unexpectedly when my son was two and my daughter still a baby.

His death opened old wounds. I drank more than ever to medicate my pain, which brought the barriers down enough for the rage inside Hyde to find an outlet that made all those close to me suffer. I wanted to stop the insanity but I didn’t know how. I was having disturbed sleep, so my GP referred me to a therapist for a while. Unfortunately, just as I was getting somewhere, addressing my past for the first time ever, she moved abroad.

Years later, we left the UK and the move unsettled us. My drinking had escalated and became my crutch. Twice I left the family home to try to resolve my dilemma alone. Through AA I managed to stop drinking twice for 18 months but struggled with the concept of a ‘higher power’: the power greater than ourselves that can restore us to sanity. Finally, over the past three years, I’ve managed to stop completely, by my own efforts.

Years later, we left the UK and the move unsettled us. My drinking had escalated and became my crutch. Twice I left the family home to try to resolve my dilemma alone. Through AA I managed to stop drinking twice for 18 months but struggled with the concept of a ‘higher power’: the power greater than ourselves that can restore us to sanity. Finally, over the past three years, I’ve managed to stop completely, by my own efforts.

During this time I visited a friend who was a recovering alcoholic. He was content and coping really well after an acrimonious divorce, fractured relationships with his kids and financial hardship. He’d told me on a previous occasion that he’d done the Process. I was bemoaning my past, as I often did, when he suddenly handed me the phone. He had tapped in the number for Hoffman and I found myself talking to the office.

After some in-depth conversations and form-filling, Hoffman decided that I needed one-to-one therapy with a therapist familiar with the course. He helped me face the darkest parts of my childhood until I felt emotionally robust enough to go on the course. I made it to the Process between lockdowns and it was an unforgettable experience.

I was with people who didn’t blame, who didn’t judge, who just listened with compassion. I couldn’t have imagined being with a group of strangers for seven days who shared their lives in such intimate detail. Thanks to them, the facilitators’ sessions and the activities, I learned ways in which I could enjoy the present, move my life forward and appreciate what I am and what I have today.

As a child, when I’d tried to share my experiences, those around me were going through similar things, so I was told to shut up, stop moaning and get on with it. It was a weakness to show vulnerability. Self-deprecating humour became my way of coping. Today, I’ve learned to recognise the kid in me to whom I can show the affection and understanding he always lacked. His anger and resentment used to determine my behaviour, but it can’t do that anymore. I’m able to step away from those patterns which gives me more control over my reactions and enables me to forge healthier relationships. I have more control over my actions and I’m more confident in making a relationship work. I try to be a better listener and like myself for it.

As a child, when I’d tried to share my experiences, those around me were going through similar things, so I was told to shut up, stop moaning and get on with it. It was a weakness to show vulnerability. Self-deprecating humour became my way of coping. Today, I’ve learned to recognise the kid in me to whom I can show the affection and understanding he always lacked. His anger and resentment used to determine my behaviour, but it can’t do that anymore. I’m able to step away from those patterns which gives me more control over my reactions and enables me to forge healthier relationships. I have more control over my actions and I’m more confident in making a relationship work. I try to be a better listener and like myself for it.

When Mr Hyde is lurking – he will always be there – I have tools and tips I picked up on the course to quieten him. I placate him by seeing the source of his unease and by giving him the reassurance that all has turned out well after all.

The Process prompted me to take steps out of my comfort zone. I’ve bought a guitar, I practice meditation and I’ve swum in the sea all through the winter months. I’m even thinking of trying some drama.

In my marriage, I try not to take things the wrong way. Most importantly, I found out that only I can change. I can’t change other people.

A friend recently said that it’s as if a dark cloud has lifted from around me. I feel relaxed and more positive about myself and my future. People have commented that I don’t dwell on my past now and live more in the present. That makes me better company. There is no place for sarcasm and cynicism in my life any more.

What else did I learn?

- None of what happened was my fault. It was normal to feel the way I felt but I can’t go through life with a victim mentality.

- The past is gone. I must move forward. Life is not a rehearsal.

- Neither of my parents were to blame. They had both had tragic childhoods. There was a lot of positive stuff to write about my Mam and even my Dad on the Process. I remember them for those things now and will always be grateful.

- I’m thankful for so much in my life today, not least that I’ve parented three children and am about to be a grandfather for the third time.

- I no longer compare the suffering of others to my own. All pain is relative.

- The Process enabled me to appreciate my life today but also to help people enjoy their own life, in spite of its ups and downs. Accepting that the child and teenager in me were former selves was a breakthrough. I’m neither of these personalities today and have a better grasp of what feeling and acting like an emotionally mature adult is. A big part of that is being able to use my own experience to hear and help others who are suffering just as I did.

We’d like to thank Brian for sharing his Process Story with the Hoffman community.

Sign up to receive monthly newsletters from Hoffman

Sign up to receive monthly newsletters from Hoffman